Cities and The Future of Fresh Water: Desalination and Deep Tunnels

It’s clear that seven billion humans cannot continue to rely on Earth’s natural cycles to provide for our increasingly urban civilization. To sustain our current and future needs, and to protect the rest of life on Earth, we need reliable systems that minimise our impact on the environment.

Clean fresh water provision and sewage treatment are two of the foundations of civilization – which together provide a huge boost in health, quality of life and productivity. Increasing demands on the natural water cycle and ageing legacy systems (that date back in some areas to Victorian or even Roman engineering) mean that new technologies and novel large-scale engineering projects are needed.

On the supply side: 96.5% of Earth’s water is locked up in the salty seas, while 40% of people on the planet already suffer from water shortage*, and half the world’s people live within 60km of a coastline* – so it’s obvious that desalination is a key water supply technology.

Advances in semi-permeable membrane production allow for fast high volume desalination, especially using reverse osmosis – where hydrostatic pressure is used to push fresh water through the membrane, leaving salts and micro-organisms safely trapped on the other side.

(*UN figures)

Even in the UK, London is at risk of water restrictions in times of drought, so the Thames Water Desalination Plant was built to offset this. The plant (in Beckton, East London) runs entirely on renewable energy and can take in brackish water from the tidal River Thames – removing salt using the reverse osmosis process to produce 150 million litres of clean fresh drinking water each day – enough for nearly one million people. Once treated the water is transferred to North East London in a new 12km long pipeline, which can hold a staggering 14 million litres of water.

Photo: London at night, from the International Space Station. Credit: NASA/JSC

(public domain)

The flip-side of sustainable water management is sewage treatment: to prevent the spread of disease, minimise pollution reaching natural waterways, and to reclaim fertilizer for agriculture. Increasingly large cities produce massive sewage flows, requiring new engineering works on a heroic scale that might surprise even the late great engineering genius Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

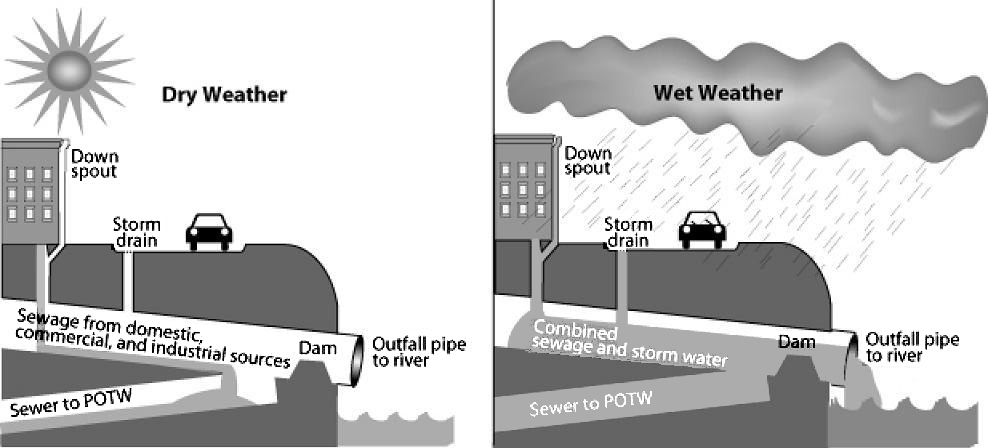

Greater London has a population of over 8.7 million people and growing, yet like many cities it still has an extensive legacy combined sewer system, which also collects surface runoff. During heavy rainstorms excess rainwater and sewage automatically overflows to prevent flooding of the sewage treatment works. These Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) now pour 39 million tonnes of mixed stormwater and untreated sewage out of the 150 year old Victorian sewer system into the River Thames and River Lea every year.

Image: Combined Sewer System. Credit: EPA (public domain)

To stop this pollution two huge tunnels are being commissioned to store the excess during storms, so it can be safely treated later: the 7.2m wide, 6.9km long Lee Tunnel is the first – it runs underneath the London Borough of Newham, from London’s largest CSO at Abbey Mills to the recently much enlarged Beckton Sewage Treatment Works.

The Lee Tunnel is London’s deepest-ever tunnel, because its shallowest point was set at 75m deep so as to capture flows from the lowest point of the massive new Thames Tideway Tunnel; a 7.2m wide, 25km long tunnel currently under construction below the River Thames – which will connect 34 of London’s most polluting CSOs to the Lee Tunnel, and hence to the Treatment Works.

While other smaller cities such as Philadelphia, USA have used various approaches under the umbrella term of Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) to tackle excess storm flows, London has six times the population and sits on layers of impermeable clays and saturated gravels that severely limit the flows SuDS methods can cope with – which is why the giant Lee and Tideway Tunnels are essential to fix London’s river pollution problem.